Who’s ready for some fucking clickbait? You? Alright, listen. I’m going to give you the answer in this first paragraph and spare you, busy and weary knowledge-seeker. The key to sucking less at things is: Incremental improvement via conscious repetition. There you go. Now you know. There’s 3,000 columns on this site already that discuss this exact concept, many of them are listicles, and I’ll bet you’ve read at least 50 of them — yet here you are staying reading.

But, I imagine those of you who know me, who know my writing style, who know that this could never only just be about that, didn’t come here for just the answers. You came here for the stories and the cussing. Well, motherfuckers, let’s do this. But first, a picture:

You just scrolled past the Japanese script for “Kaizen.” (I know, I know. You’ve probably read that word before, too.) The rough literal translation in English is “improvement.” The philosophical translation a bit more closely resembles the Latin “Excelsior” — which I’m only aware of because:

A. It was my home state’s (New York) motto.

B. This scene in Silver Linings Playbook where Jennifer Lawrence won my heart.

Kaizen essentially means “perpetual incremental improvement,” or the idea of doing some small things a little bit better each day. The idea is if you keep practicing Kaizen, eventually excellence becomes baked into your default.

The more sexy approximation of this is Malcolm Gladwell’s “10,000 hours,” whereby if you’ve been doing any one thing for 10,000 hours, you’ll eventually master it. I believe this is a gross oversimplification, because it sorta implies that you’ll become good at something via the mere act of doing it. Doing something is not nearly the same as improving at something. Improving requires intent, mindfulness and a host of other Eastern doctrines that have been bastardized by yoga studios across the country.

I’ve been running for 17 years, and I’m not a whole lot better at it now than I was then. I can chalk this up to my “intention” I set every time I go out and run: I simply lace up the shoes and put in some miles until I feel tired. I still run about an 11-minute mile when I push myself — which is about what I was doing at age 20, 25, and 30. This ain’t Kaizen. It’s just action.

In parallel, I’ve also been playing guitar for 17 years. For the first 2–3 years, I improved quite a great deal; I sat at home and memorized Oasis and Dave Matthews Band (I know, I know …) until I developed a steady enough bank of chords and riffs that I could infuse into my own songwriting. I haven’t done much practicing since. I simply strap on the guitar, “lace ’em up” and perform for people about once a week. I’ve unquestionably played for 10,000 hours — and I’m not the Beatles. That ain’t Kaizen, either. It’s just action.

People close to me will be quick to note that I’ve run 10 half-marathons and a few other races, and they’d also note that I’ve played over 500 shows in the Austin area. Clearly I must be getting “better” at these things, or I would still be sitting on the sidelines instead of hitting the pavement, or practicing at home instead of playing paying gigs in front of hundreds (okay, like 17) people. To a degree, they’re right.

I’m a better performer now than I was a decade ago, or even five years ago. And I’m a better racer now than I was a decade ago, or even five years ago. That’s where the Kaizen comes in: Getting better at specific things you do by knowing what to expect, how to handle things when they go wrong, and just getting more comfortable and less nervous each successive time you put yourself on the line for anything.

Now I’ll give you another highly relevant example of “Kaizen” from my own life: This is the very first sports column I ever wrote. It’s from 2007. I had never written before, but I wanted to, so I went out and got myself an unpaid gig at a blog. It’s readable, but it’s not very good, and it took me about three hours and 12 rounds of edits to work it into its final form.

This is the last sports column I ever wrote (and it’s not even really about sports). It ran in Sports Illustrated. It took 20 minutes and one edit to work into its final form. It became the most widely-read piece I’d ever written at the time. The improvement is obvious. It’s tighter, it’s more poetic, the sentences are sharper and deeper. There aren’t punctuation errors. Plus, the words came way easier and from a wiser, deeper place than they did eight years ago.

I improved as a writer by actually sitting at home, reading writers I loved, deconstructing their ideas, and studying their sentence structure, paragraph formations, word choices and so on. I write — and this is the key here — nearly every damn day. I write with vigorous intent to make each successive column better and more thoughtful than the last. (Author’s Note: Except this piece you’re currently reading, which is a self-indulgent brain dump.)

Now, back to running. On January 8, 2017, I ran the Dopey Challenge at Walt Disney World, which was four races over four days: a 5K, a 10K, a half-marathon and a full marathon. You may remember me talking about this.I had never run a full marathon before, so I had no choice but to improve. It required small, incremental improvements in diet, mileage, and speed and an elimination of my myriad wasteful habits that don’t serve the larger purpose: It required Kaizen.

Doing things in life — like playing music, running marathons and writing sports columns that people actually want to read — is an astonishing rush of awesome. It’s an accomplishment. It shouldn’t be discounted. But, while achievements may give you accolades, they don’t necessarily make you a better person because you did them. They make you a person who did things. Only when those things are a result of sustained, perpetual effort and improvement does it signify “progress.” This is the only way you can ever suck less at things.

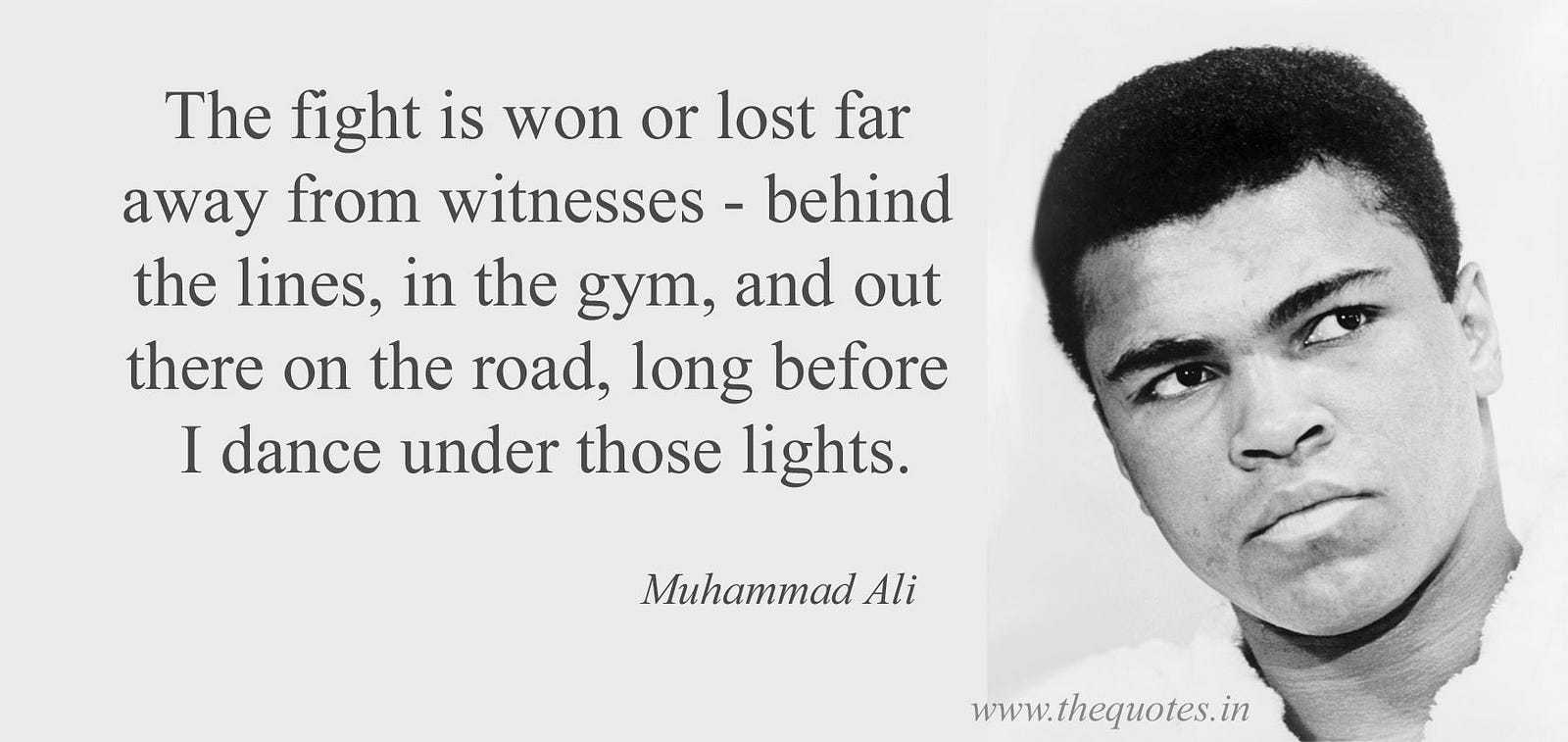

Take it from The Greatest Of All Time:

Seek to master your time in the gym, to really set your intentions for improvement, and you won’t be able to wait to dance under those lights.

Excelsior, Excelsior.

Recent Comments